uncondemned entrails*

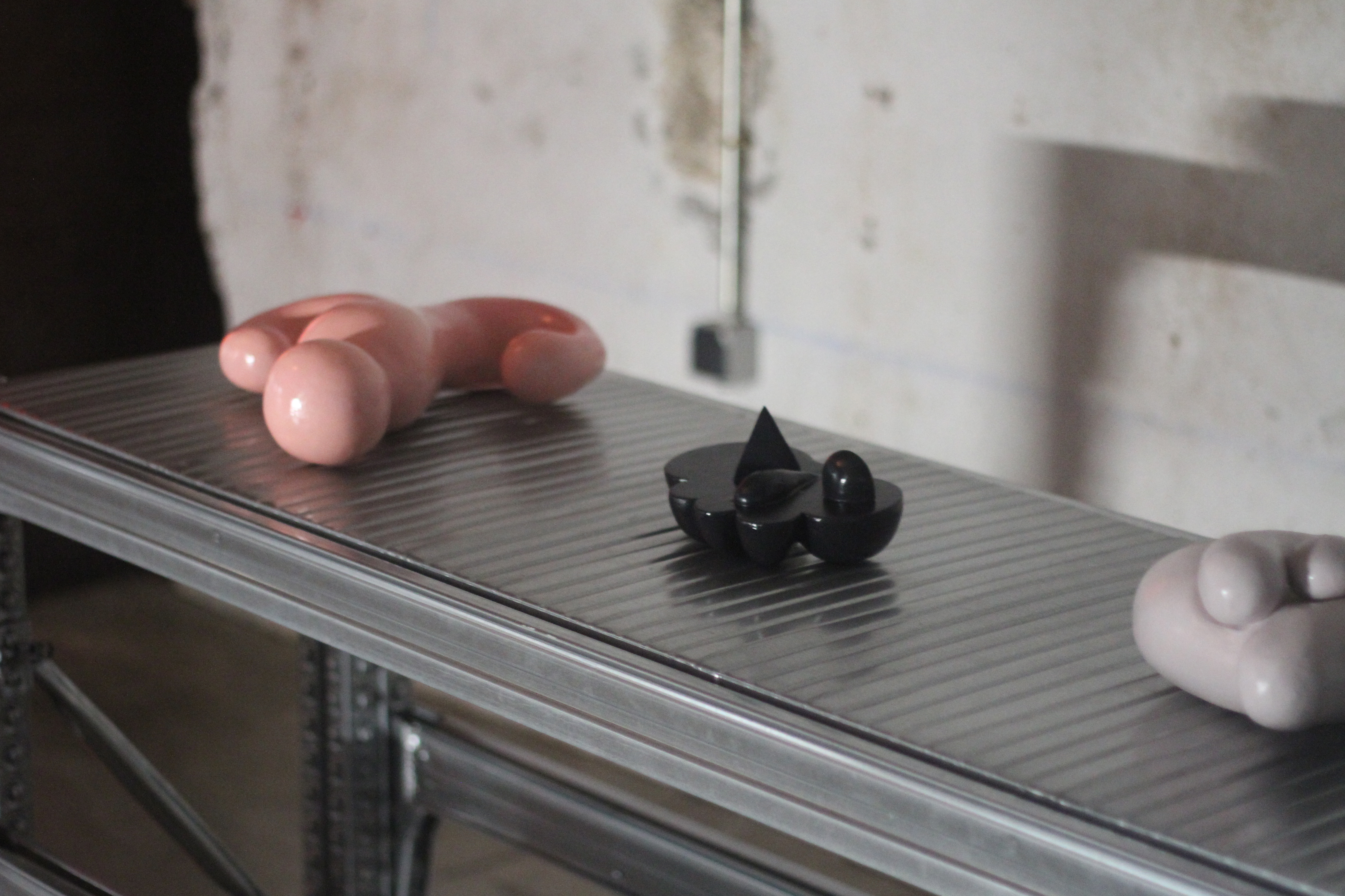

Fig. #01. Installation view at Matadero (Madrid) for Uncondemned Entrails. Photo credits: Lisa Mazenauer, 2023.

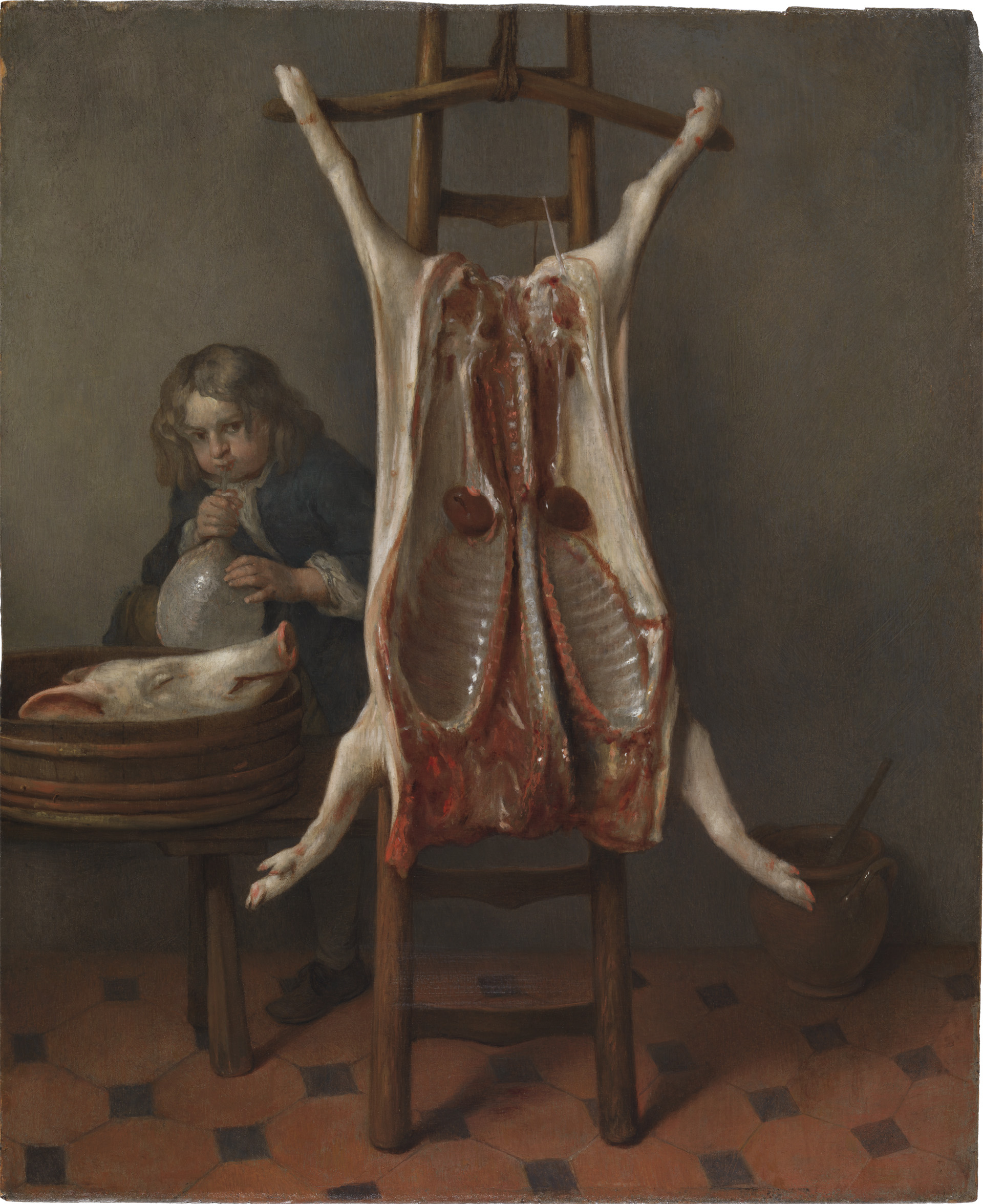

‘Uncondemned Entrails’ investigates the abusive history of slaughters and judgement of dead animals’ carcasses inside of abattoirs: a series of brutal post-mortem practices that are still being perpetrated nowdays for the satisfaction of human consumers. The project addresses — and recontextualizes — the relevance of Aruspicina in utilizing theoretical models of animal organs as tools to expose and narrate ghostly paradigms of death and violence towards bodies and corpses, along with the implications such patterns have on the lives of human- and other-than-human-kinds.

In doing so, the researcher becomes the haruspex itself who, by designing and displaying postnatural entrails to a public, unveils histories of extractive abuse perpetrated by humans upon other organisms. The project is part of the collective exhibition “we?” curated by the Institute for Postnatural Studies at Matadero’s Intermediae Lab in Madrid, in occasion of the first Postnatural Independent Program.

Fig. #03. Project for a slaughterhouse and livestock market in Madrid. Luis Bellido y Gonzáles, 1914. For more than six decades, between 1924 and 1996, around 400 and 500 oxen and 5000 sheep were killed every day in this space.

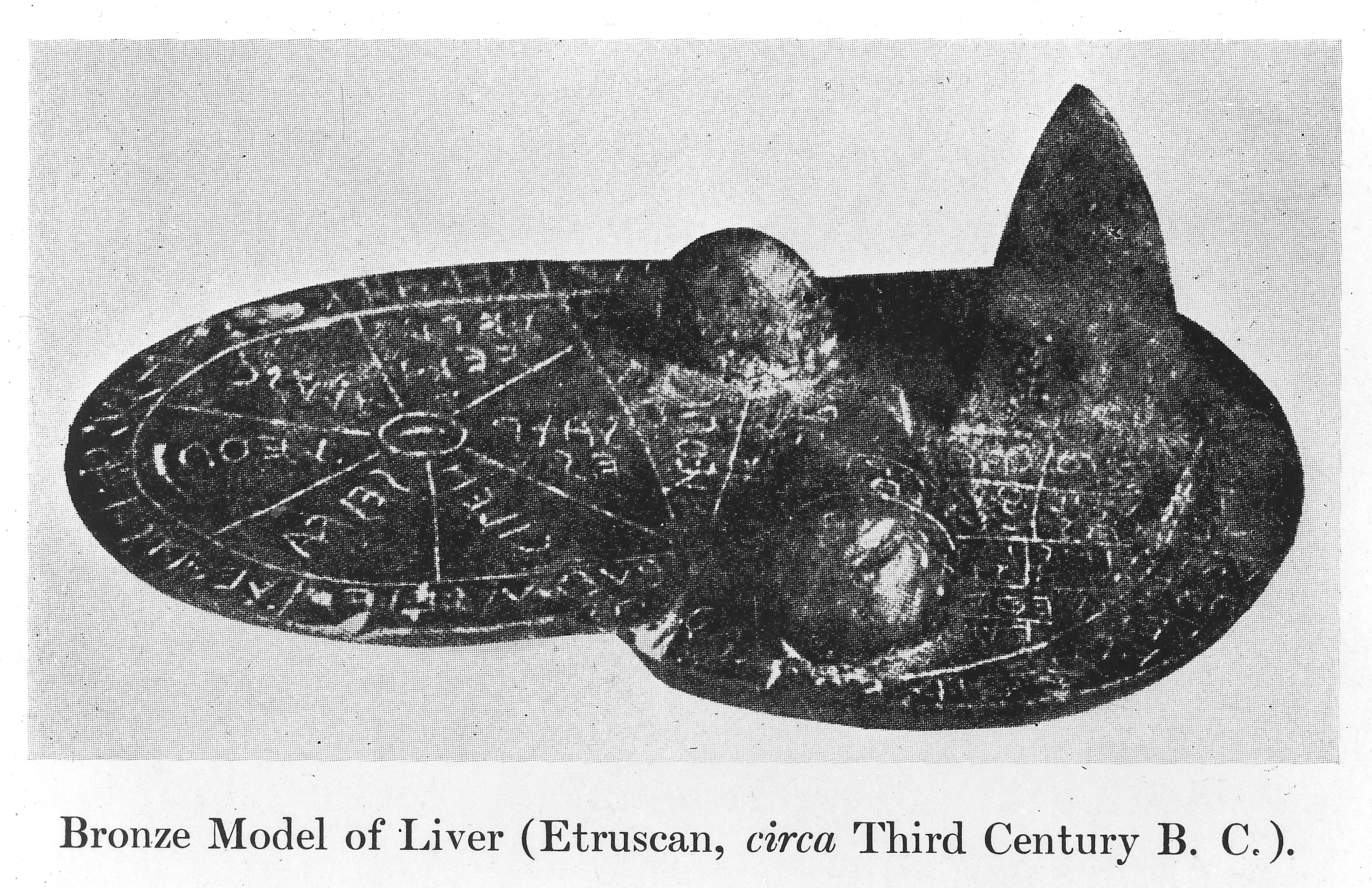

Aruspicina is the art of reading the entrails of dead animals as a divinatory practice to understand the future. This gruesome process was a performative ritual developed by the Etruscans, a population that lived in Italy between the 9th and the 1st Century B.C., who believed that due to the close relationship between the macro- and the microcosm, the distribution of the celestial vault – which regulated their political system – was also reflected on the Earth’s individual elements, both living and non-living. But what do death and dead organisms have to do with politics in a postnatural ecosystem?

Donna Haraway eviscerates this concept while describing the Chthulucene, a new era in which all critters live and “die together”, as if it was an other form of being (interdependently) rather than as a form of non-existence: a way to intertwine and mold the fleshes between different species in a perpetual process of co-generation. If our human bodies are shared with the world, if there are no boundaries between humans and other species, then our-body politics become every-body politics (and viceversa). And if we change the way we understand and administrate dead bodies, we can also change how we conceive and manage the living ones.

The installation exhibited at Matadero displays three geometrical reproductions of animal organs — a cow uterus; a sectioned portion of a pig’s liver; a lamb’s digestive tract — designed along the line of the “Fegato di Piacenza”, a bronze model of sheep’s liver with Etruscan inscriptions, used by haruspex priests to perform divination practices. The organs on display are presented as ‘perfected’ copies of the original animal entrails: designed as speculative tools with which contemporary haruspices (slaughterhouse laborers) are enabled to judge dead carcasses of animals during routine meat inspections, just as stated in FAO’s 1995 ‘Manual of Meat Inspection for Developing Countries’:

“Routine postmortem examination of a carcass should be carried out as soon as possible after the completion of dressing in order to detect any abnormalities so that products only conditionally fit for human consumption are not passed as food. [...] Trimming or condemnation may involve: (1) any portion of a carcass or a carcass that is abnormal or diseased; (2) any portion of a carcass or a carcass affected with a condition that may present a hazard to human health; (3) any portion of a carcass or a carcass that may be repulsive to the consumer.”

In occasion of the public program on July 14th, 2023 the central stage at Intermediae Lab hosted my lecture “Uncondemned Entrails”, which was supposed to work as a complementary piece to the installation. The panel was designed as a performative talk in which the speaker impersonated, both in the way of dressing and acting, the role of a modern haruspex from the slaughterhouse working class. The performance aimed to re-evoke past abusive processes and judgement of animals’ corpses, starting from the three sculptures displayed in front of the main stage. After declaring a selection of guidelines from FAO’s ‘Manual’, the performance concluded with an extract from Bataille’s Erotism (1957) about the sacrificial violence of abattoirs, characterized by “[...] atmospheres of surging carnal life”.

Link to VIMEO︎︎︎.

Fig. #14.

Uncondemned Entrails performance/talk footage from “we?”’s public program. Photo credits: Sol Archer, 2023.

Fig. #14.

Uncondemned Entrails performance/talk footage from “we?”’s public program. Photo credits: Sol Archer, 2023.